The Pirate Cinema: a Generative Self Portrait

The Pirate Cinema: a Generative Self Portrait

In the framework of the project Masters & Servers. Networked Cultures in the Post-Digital Age, the Link Art Center commissioned Matteo Cremonesi, the Link Cabinet curator, an essay about The Pirate Cinema, the project by French artist Nicolas Maigret presented in the Cabinet from March 4 to 28, 2015. Have a nice reading!

Creating a point of contact between two or more people, or sending a message, regardless of the form or content, are actions of great significance, as well as a basic human need. The act of communication in its many forms has long been the focus of many artists. One key example was undoubtedly Mail Art. For the artists involved, Mail Art was a fascinating opportunity to create a genuine network of people, individuals who got actively involved in the process of sending letters, postcards and fanzines to each other. In 1980, the artists Kit Galloway and Sherrie Rabinowitz produced their famous Hole in Space project that for three days created a live video link between the Lincoln Center in New York and the Broadway Store in Los Angeles. The work was a kind of experiment that observed how the opportunity for live communication between people on opposite sides of the United States could change the way in which they interacted, and give rise to entirely new ways of communicating. In 1997 the duo of artists known as MTAA created Simple Net Art Diagram, a basic animated gif showing two stylized computers connected by a cable with a flashing red lightning bolt, with the caption “The art happens here”. The image highlights the centrality of the communicative act for artists in the second half of the 90s who were close to the artistic practices of Net Art: the internet was an opportunity to create interconnected networks of computers and users all round the world. [1] In this context, peer-to-peer networks began to enjoy increasing popularity, enabling users to make available and share all kinds of files and content with others. These communication tools enabled people to create networks to exchange not only messages and information, but also different types of materials.

This scenario clearly shows how both the communicative act itself – creating connections among multiple individuals – and the act of sharing materials of different kinds, is not a neutral act, but one charged with meaning.

On closer inspection, exchanging data on peer-to-peer networks is not even neutral from a purely technical point of view: the act of sharing and sending files actually temporarily modifies and rearranges the files themselves. This system of sharing breaks the files down into tiny fragments that, taken singly, would not mean anything to the user: tiny packets of information that are sent to the receiver in entirely random order. Only once the whole file has been transferred are the packets reassembled in their initial order, making the file accessible and readable.

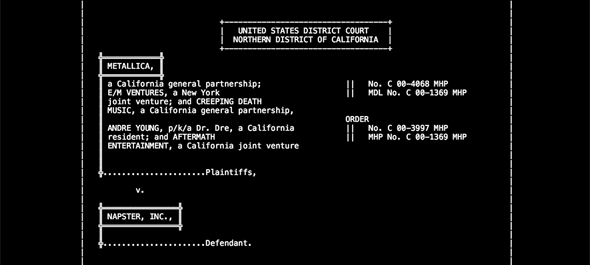

This transition from one point to another in a channel of communication is the focus of The Pirate Cinema, a work by the French artist Nicolas Maigret. The project, which he started in 2012, has taken different forms: initially an installation, it was later presented as a live performance, then an online version was created. The exhibition in the online gallery Link Cabinet [2] in March 2015 featured yet another version of the project, based on the famous legal dispute between Metallica and Napster in the early 2000s. It was the first time that artists had sued a company supplying software for peer-to-peer file sharing, and the ensuing court case led to the closure of Napster. The artist’s project inspired by this takes the form of streaming audio based on the live monitoring of Metallica albums being shared online.

The Pirate Cinema is a real-time streaming of files being swapped on the peer-to-peer system BitTorrent, and the result could be described as a generative portrait of data sharing dynamics in this kind of user network. The work visualises the technical dynamics of data exchanges, manifesting a mechanism that is not normally visible to the common user. The Pirate Cinema focuses in particular on the exchange of video files, monitors the activity of BitTorrent users and identifies the hundred most shared files, showing the few seconds of video that correspond to each data packet sent. The clips appear in the same order in which they are transmitted on BitTorrent, therefore completely at random. [3] What we are shown by Maigret radically compromises the integrity of the individual files, making it impossible to follow plots, stories or narratives of any kind: by embracing the peer-to-peer system’s random transmission mode, the individual files are not only broken up, but also mashed together with fragments of all the other files that the system is monitoring at that time. In a lecture at Aksioma Project Space, Geoff Cox [4] described The Pirate Cinema as real-time monitoring in video form of the life of the network, and a representation of the complexity and temporal stratification which characterises the modern world and the many ways of being live and in time. The result is an offbeat live stream with marked and inevitable echoes of the glitch aesthetic, that is extremely effective in both conceptual and visual terms: a clear, immediately comprehensible rendering of a technical process that would be much more difficult to explain in words.

The Pirate Cinema is a continuous stream of images, sounds, data, information, but also fragments of stories and narratives, a mishmash of arthouse, b-movie and porn scenes, a flood of crazed graphics and pixels. This relentless river of content generates two contrasting visions of the flow concept. On the one hand, there is the idea of flow as a constant stream – or rather, streaming – namely the transmission of live data from a provider, in this case one of the users sharing materials on a peer-to-peer network, to other users wishing to obtain and view the contents. Maigret’s work shows how this large mass of content continues to flow steadily across the ether and enables us to observe it in progress; to sit back and enjoy the endless, ever-changing sequence of material on the screen. Yet this notion of an ongoing stream is opposed by the fragmentation of the individual files: the flow is continually being interrupted, truncated. Be they films, tv series or simply music tracks, each file is originally structured according to its own logic, with its own internal order, which may be more or less fixed, sequential and narrative to varying degrees, but is nonetheless an order decided and imposed by its creator. What The Pirate Cinema shows is a deconstruction – albeit temporary – of the content shared by the users that, as we have said, reflects the workings of peer-to-peer file sharing systems. Yet it does more than simply dismantle the source material: it generates new possibilities, giving rise to something novel and different. The flow generated by Maigret is not simply a collage of small fragments of audio and video files, but new content with a meaning of its own, independent of the source material. [5] This can be seen as a tribute to copy culture and the practice of remixing in general, that the artist has a personal connection with, and that has played a key role in shaping digital cultures over the last thirty years. [6]

There is something fascinating and mesmerizing about the relentless flow generated by the software programme, which gets almost hypnotic over time: something to do with a mixture of curiosity, the awareness of watching a show that never ends, and that is ever-changing and constantly new and different, and our unspoken attempts to identify meaningful patterns that would create some kind of relationship between the clips. Absorbed in the huge amount of material that scrolls rapidly before us, it is easy to understand how Maigret’s work can be viewed as a metaphor for the modern-day relationship between the user and the huge mass of data that is constantly available online. The way we access information online is becoming increasingly convulsive, rapid and fragmented: we hop from one piece of content to the next, switching back and forth between a slew of open browser pages that present a variety of different contents; we keep several social media conversations on the go at once, chatting to friends or colleagues, and making plans for the weekend while we discuss important work-related issues. We skip from gossip sites to articles on scientific trivia or the latest technological gizmo while we are trying to finish a job that is already past its deadline. In exactly the same way, The Pirate Cinema lets us spend a few seconds watching one scene before jumping immediately to the next, creating a random path that continues ad infinitum and is impossible to trace.

While the project creates a generative portrait that aims to paint an impartial picture of a given technology, it is interesting to note how our attitudes, as humans, and the ways we use technology, are now increasingly resembling the operative dynamics of these very tools. It is a process in which the two parties, man and machine, inevitably influence one another, and where it is impossible and perhaps not even that interesting to try and pinpoint exactly who is exerting an influence on who, in what is basically a chicken and egg situation. Yet it is undeniably fascinating to consider how these two worlds – that we continue to view as separate or even opposing – are drawing ever closer and influencing one another more and more.

However while it is difficult to identify logical, intrinsically coherent patterns in our online movements, habits, visits and readings, this does not mean that we are not leaving a trace. Quite the opposite. Our movements leave tracks that we are unlikely to be able to conceal or delete. Once again, Maigret’s work makes an interesting point, highlighting how it is possible to trace exact data and information regarding the individuals who use the file sharing systems in question. In addition to the streaming video, the work contains elements that we might tend to overlook or underestimate at first glance, when we are immersed in the whirlwind of images on the screen. The sequence of digits, alphanumeric codes and titles that are superimposed on the streamed images are in actual fact a series of extremely precise data regarding the files being shown, such as the name of the file and the torrent it is associated with, but above all the IP addresses and geographical origins of the users who are doing the sharing. [7] At this point The Pirate Cinema becomes, to all intents and purposes, a collective performance with a double layer of unawareness. On one level there is the unwitting participation of the BitTorrent users who end up in the area being monitoring by the artist, while on another there is the fact that they are not aware they are being tracked by BitTorrent, and having their file sharing activities publicly displayed by Maigret. In the current social and political context, characterised by hyper-control and hyper-surveillance, Maigret’s work reflects on the vulnerability of systems we use on a daily basis, yet without the due awareness.

The Pirate Cinema could be seen as a literal interpretation of the slogan “The art happens here” from Simple Net Art Diagram, thus becoming a bona fide work of Net Art; a work in which the artist seeks to provide a snapshot of the complexity of the present, identifying a topic and a setting – the online activities we all carry out on a daily basis – that is a starting point for broader musings. The artist does not set out to provide any answers, but has the merit of highlighting, both directly and metaphorically, situations and contradictions that affect all of us and the social, political and economic setting we live in. As if to say that to understand who we are, all we need to do is look at the list of torrent files we are sharing: just sit back and watch, and try to catch our reflection in the screen.

Notes

[1] A concept that was also succinctly expressed by Olia Lialina in the foreword to Digital Folklore: “net art” (where “net” was more important than “art”” (O. Lialina, D. Espenschied, ed., Digital Folklore, Merz&Solitude, 2009).

[2] Link Cabinet is a project by Matteo Cremonesi for Link Art Center, a single web page designed to host personal exhibitions, in which each artist presents a single, site-specific work. linkcabinet.eu

[3] For further discussion on this mechanism see the interview: Marie Lechner, “Nicolas Maigret: ‘montrer le flux numérique ò l’échelle mondiale’”, in Libération, 8 October 2013. Available online here.

[4] Geoff Cox, “Real-time for Pirate Cinema”, Aksioma | Project Space, Ljubljana. 21 January 2015. A video of the presentation is available online.

[5] Describing this aspect of the work Cox, refers to Eisenstein’s montage theory, and how the juxtaposition of disparate images and scenes can generate meaning.

[6] In an interview for Filmmaker Magazine, Maigret elaborates on Copy Culture, asserting that peer-to-peer networks also play an important role as a source of film materials that are rare or hard to track down. In Randy Astle, “transmediale 2015: Nicolas Maigret, BitTorrent and The Pirate Cinema”, in Filmmaker Magazine, January 2015, online here. A similar theory is maintained by Hito Steyerl in his essay “In Defence of the Poor Image”: in Steyerl, H., The Wretched of the Screen, Sternberg Press, 2012.

[7] For further discussion on the geographical aspect of the project see: Régine Debatty, “The Pirate Cinema, A Cinematic Collage Generated by P2P Users”, in We Make Money Not Art, 18 May 2013, online here.

Credits

Translated from Italian by Anna Rosemary Carruthers

This text is part of Masters & Servers. Networked Cultures in the Post Digital Age, a joint project by Aksioma (SI), Drugo more (HR), Abandon Normal Devices (UK), Link Art Center (IT) and d-i-n-a / The Influencers (ES) that was awarded with a Creative Europe 2014 – 2020grant. For 24 months from September 2014, Masters & Servers will explore networked culture in the post-digital age.

This project has been funded with support from the European Commission. This communication reflects the views only of the author, and the Commission cannot be held responsible for any use which may be made of the information contained therein.